Which of the Following Is Not a Correct Statement About Islamic Art?

Islamic Fine art

Islamic art encompasses visual arts produced from the seventh century onwards past culturally Islamic populations.

Learning Objectives

Identify the influences and the specific attributes of Islamic art

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Islamic art is not art of a specific religion, fourth dimension, place, or of a unmarried medium . Instead information technology spans some 1400 years, covers many lands and populations, and includes a range of artistic fields including compages, calligraphy , painting, glass, ceramics , and textiles, among others.

- Islamic religious art differs from Christian religious fine art in that information technology is non-figural considering many Muslims believe that the depiction of the homo form is idolatry , and thereby a sin against God, forbidden in the Qur'an. Calligraphy and architectural elements are given of import religious significance in Islamic art.

- Islamic art adult from many sources: Roman, early on Christian art, and Byzantine styles ; Sassanian art of pre-Islamic Persia; Fundamental Asian styles brought past diverse nomadic incursions, and Chinese influences appear on Islamic painting, pottery , and textiles.

Key Terms

- Qu'ran: The primal religious text of Islam, which Muslims believe to be the verbatim word of God (Arabic: Allah). It is widely regarded every bit the finest slice of literature in the Standard arabic language.

- arabesque: A repetitive, stylized pattern based on a geometrical floral or vegetal blueprint.

- idolatry: The worship of idols.

- monotheistic: Believing in a single god, deity, spirit, etc., especially for an religion, organized religion, or creed.

Islam

Islam is a monotheistic and Abrahamic religion articulated by the Qur'an, a book considered by its adherents to exist the verbatim give-and-take of God (Allah) and the teachings of Muhammad , who is considered to be the final prophet of God. An adherent of Islam is called a Muslim.

Most Muslims are of two denominations: Sunni (75–ninety%),[seven] or Shia (ten–20%). Its essential religious concepts and practices include the five pillars of Islam, which are basic concepts and obligatory acts of worship, and the following of Islamic constabulary, which touches on every aspect of life and lodge. The 5 pillars are:

- Shahadah (belief or confession of organized religion)

- Salat (worship in the form of prayer)

- Sawm Ramadan (fasting during the month of Ramadan)

- Zakat (alms or charitable giving)

- Hajj (the pilgrimage to Mecca at to the lowest degree once in a lifetime)

Islamic Art

Islamic art encompasses the visual arts produced from the seventh century onward past both Muslims and non-Muslims who lived within the territory that was inhabited by, or ruled by, culturally Islamic populations. It is thus a very difficult art to define because it spans some 1400 years, covering many lands and populations. This fine art is besides non of a specific religion, fourth dimension, place, or single medium. Instead Islamic fine art covers a range of artistic fields including compages, calligraphy, painting, glass, ceramics, and textiles, amidst others.

Islamic fine art is non restricted to religious art, but instead includes all of the art of the rich and varied cultures of Islamic societies. Information technology often includes secular elements and elements that are forbidden by some Islamic theologians. Islamic religious fine art differs profoundly from Christian religious art traditions.

Considering figural representations are generally considered to be forbidden in Islam, the give-and-take takes on religious meaning in art equally seen in the tradition of calligraphic inscriptions. Calligraphy and the decoration of manuscript Qu'rans is an of import aspect of Islamic fine art as the give-and-take takes on religious and artistic significance.

Islamic architecture, such as mosques and palatial gardens of paradise, are also embedded with religious significance. While examples of Islamic figurative painting do exist, and may cover religious scenes, these examples are typically from secular contexts, such equally the walls of palaces or illuminated books of verse.

Other religious fine art, such as drinking glass mosque lamps, Girih tiles, woodwork, and carpets ordinarily demonstrate the same manner and motifs every bit gimmicky secular art, although they exhibit more prominent religious inscriptions.

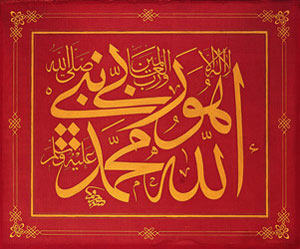

A calligraphic panel by Mustafa Râkim (tardily 18th–early 19th century): Islamic art has focused on the depiction of patterns and Standard arabic calligraphy, rather than on figures, because it is feared by many Muslims that the depiction of the human form is idolatry. The panel reads: "God, there is no god but He, the Lord of His prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) and the Lord of all that has been created."

Islamic fine art was influenced past Greek, Roman, early Christian, and Byzantine fine art styles, as well as the Sassanian fine art of pre-Islamic Persia. Key Asian styles were brought in with various nomadic incursions; and Chinese influences had a formative effect on Islamic painting, pottery, and textiles.

Themes of Islamic Art

There are repeating elements in Islamic art, such as the use of stylized , geometrical floral or vegetal designs in a repetition known as the arabesque . The arabesque in Islamic art is often used to symbolize the transcendent, indivisible and infinite nature of God. Some scholars believe that mistakes in repetitions may be intentionally introduced as a show of humility by artists who believe just God can produce perfection.

Arabesque inlays at the Mughal Agra Fort, Bharat: Geometrical designs in repetition, know as Arabesque, are used in Islamic art to symbolize the transcendent, indivisible, and infinite nature of God.

Typically, though non entirely, Islamic fine art has focused on the depiction of patterns and Standard arabic calligraphy, rather than homo or animal figures, because information technology is believed by many Muslims that the depiction of the human form is idolatry and thereby a sin against God that is forbidden in the Qur'an.

Nonetheless, depictions of the human class and animals can be found in all eras of Islamic secular art. Depictions of the human being form in fine art intended for the purpose of worship is considered idolatry and is forbidden in Islamic law, known every bit Sharia law.

Islamic Architecture

Islamic architecture encompasses a wide range of styles and the principal example is the mosque.

Learning Objectives

Describe the evolution of mosques, and their dissimilar features during different periods and dynasties

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- A specifically recognizable Islamic architectural style emerged before long after Muhammad's time that incorporated Roman edifice traditions with the addition of localized adaptations of the former Sassanid and Byzantine models.

- The Islamic mosque has historically been both a place of prayer and a customs coming together space . The early on mosques are believed to exist inspired past Muhammad's domicile in Medina, which was the first mosque.

Primal Terms

- mosque: A place of worship for Muslims, corresponding to a church or synagogue in other religions, ofttimes having at least one minaret. In Arabic: masjid.

- mihrab: A semicircular niche in the wall of a mosque, that indicates the qibla (direction of Mecca), and into which the imam prays.

- minaret: The alpine slender belfry of an Islamic mosque, from which the muezzin recites the adhan (call to prayer).

Islamic Compages

Islamic architecture encompasses a broad range of both secular and religious styles. The principal Islamic architectural case is the mosque. A specifically recognizable Islamic architectural fashion emerged shortly after Muhammad'due south time that incorporated Roman building traditions with the addition of localized adaptations of the former Sassanid and Byzantine models.

Early Mosques

The Islamic mosque has historically been both a place of prayer and a community meeting infinite. The early mosques are believed to exist inspired past Muhammad'due south home in Medina, which was the showtime mosque.

The Smashing Mosque of Kairouan (in Tunisia) is one of the best preserved and most significant examples of early great mosques. Founded in 670, it contains all of the architectural features that distinguish early mosques: a minaret , a large courtyard surrounded past porticos , and a hypostyle prayer hall.

Dome of the mihrab (9th century) in the Great Mosque of Kairouan, also known every bit the Mosque of Uqba, in Kairouan, Tunisia: This is considered to be the ancestor of all the mosques in the western Islamic world.

Ottoman Mosques

Ottoman mosques and other architecture beginning emerged in the cities of Bursa and Edirne in the 14th and 15th centuries, developing from before Seljuk Turk architecture, with additional influences from Byzantine, Western farsi, and Islamic Mamluk traditions.

Sultan Mehmed II would subsequently fuse European traditions in his rebuilding programs at Istanbul in the 19th century. Byzantine styles as seen in the Hagia Sophia served as peculiarly important models for Ottoman mosques, such as the mosque constructed by Sinan.

Edifice reached its summit in the 16th century when Ottoman architects mastered the technique of edifice vast inner spaces surmounted past seemingly weightless yet incredibly massive domes , and achieved perfect harmony betwixt inner and outer spaces, equally well every bit articulated light and shadow.

They incorporated vaults , domes, square dome plans, slender corner minarets, and columns into their mosques, which became sanctuaries of transcendently aesthetic and technical balance, as may be observed in the Blue Mosque in Istanbul, Turkey.

The Blue Mosque, Istanbul, Turkey: The Blue Mosque represents the culmination of Ottoman construction with its numerous domes, slender minarets and overall harmony.

Architecture flourished in the Safavid Dynasty , attaining a high indicate with the building program of Shah Abbas in Isfahan, which included numerous gardens, palaces (such as Ali Qapu), an immense bazaar, and a large imperial mosque. Isfahan, the upper-case letter of both the Seljuk and Safavid dynasties, bears the about prominent samples of the Safavid architecture, such as the the Imperial Mosque, which was constructed in the years after Shah Abbas I permanently moved the capital at that place in 1598.

Majestic Mosque, Isfahan, Iran: Isfahan, the capital of both the Seljuk and Safavid dynasties, bears the most prominent samples of the Safavid architecture.

Islamic Glass Making

Glassmaking was the most important Islamic luxury art of the early Middle Ages.

Learning Objectives

Describe the art of Islamic drinking glass

Primal Takeaways

Central Points

- Betwixt the 8th and early 11th centuries, the emphasis in luxury glass was on effects achieved by manipulating the surface of the glass, initially by incising into the glass on a wheel, and after by cutting away the groundwork to leave a pattern in relief .

- Lustre painting uses techniques like to lustreware in pottery and dates dorsum to the 8th century in Egypt; it became widespread in the twelfth century.

Key Terms

- luxury arts: Highly decorative goods made of precious materials for the wealthy classes.

- glassmaking: The craft or industry of producing glass.

Islamic Drinking glass

For most of the Heart Ages , Islamic luxury glass was the most sophisticated in Eurasia , exported to both Europe and Prc. Islam took over much of the traditional glass-producing territory of Sassanian and Ancient Roman drinking glass. Since figurative decoration played a pocket-sized function in pre-Islamic drinking glass, the alter in style was not precipitous—except that the whole area initially formed a political whole, and, for instance, Farsi innovations were now most immediately taken upward in Egypt.

For this reason it is frequently incommunicable to distinguish betwixt the various centers of product (of which Arab republic of egypt, Syria, and Persia were the most of import), except by scientific analysis of the material, which itself has difficulties. From various documentary references, glassmaking and glass-trading seems to take been a specialty of the Jewish minority.

Betwixt the 8th and early 11th centuries, the emphasis in luxury drinking glass was on furnishings accomplished by manipulating the surface of the glass, initially past incising into the glass on a wheel, and afterwards by cut away the background to leave a design in relief. The very massive Hedwig spectacles, only institute in Europe, but usually considered Islamic (or perchance from Muslim craftsmen in Norman Sicily), are an example of this, though they are puzzlingly late in appointment.

These and other glass pieces probably represented cheaper versions of vessels of carved rock crystal (clear quartz)—themselves influenced by before glass vessels—and there is some evidence that at this period glass and hard-stone cutting were regarded equally the same craft. From the twelfth century, the glass industry in Persia and Mesopotamia declined, and the main production of luxury glass shifted to Egypt and Syria. Throughout this period, local centers fabricated simpler wares, such as Hebron glass in Palestine.

The Luck of Edenhall: This is a 13th-century Syrian beaker, in England since the Eye Ages. For most of the Center Ages, Islamic glass was the most sophisticated in Eurasia, exported to both Europe and China.

Lustre painting

Lustre painting, past techniques like to lustreware in pottery, dates back to the 8th century in Egypt, and involves the application of metallic pigments during the drinking glass-making process. Another technique used by artisans was decoration with threads of glass of a different color, worked into the main surface, and sometimes manipulated by combing and other effects.

Gilded, painted, and enameled glass were added to the repertoire, as were shapes and motifs borrowed from other media , such as pottery and metalwork . Some of the finest work was in mosque lamps donated past a ruler or wealthy human being.

As decoration grew more elaborate, the quality of the basic glass decreased, and it oft exhibited bubbling and a brown-yellow tinge. Aleppo ceased to be a major middle after the Mongol invasion of 1260, and Timur appears to accept concluded the Syrian glass manufacture around 1400 by carrying off the skilled workers to Samarkand. By about 1500, the Venetians were receiving large orders for mosque lamps.

Some of the finest piece of work was in mosque lamps donated past a ruler or wealthy man. As decoration grew more elaborate, the quality of the basic drinking glass decreased, and it often exhibited bubbles and a brownish-yellow tinge. Aleppo ceased to be a major eye later the Mongol invasion of 1260, and Timur appears to have concluded the Syrian manufacture around 1400 past carrying off the skilled workers to Samarkand. By about 1500, the Venetians were receiving large orders for mosque lamps.

Mosque lamp: Produced in Egypt, c. 1360.

Islamic Calligraphy

Calligraphic blueprint was omnipresent in Islamic fine art in the Middle Ages, and is seen in all types of art including compages and the decorative arts.

Learning Objectives

Explicate the purpose and characteristics of Islamic calligraphy

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- In a religion where figural representations are considered an deed of idolatry , it is no surprise that the discussion and its artistic representation became an important aspect in Islamic art.

- The primeval form of Standard arabic calligraphy is Kufic script .

- Besides Quranic verses, other inscriptions include verses of poetry, and inscriptions recording buying or donation.

Cardinal Terms

- Kufic script: The earliest class of Arabic calligraphy, noted for its angular class.

- calligraphy: The art of writing letters and words with decorative strokes.

In a religion where figural representations are considered an act of idolatry, it is no surprise that the word and its artistic representation became an important aspect in Islamic fine art. The most important religious text in Islam is the Quran, which is believed to exist the word of God. At that place are many examples of calligraphy and calligraphic inscriptions pertaining to verses from the Quran in Islamic arts.

9th century Quran: This early on Quran demonstrates the Kufic script, noted for its angular course and as the earliest class of Standard arabic calligraphy .

The primeval form of Arabic calligraphy is Kufic script, which is noted for its athwart grade. Standard arabic is read from right to left and only the consonants are written. The blackness ink in the image higher up from a 9th century Quran marks the consonants for the reader. The red dots that are visible on the page notation the vowels.

However, calligraphic pattern is not limited to the book in Islamic fine art. Calligraphy is found in several unlike types of art, such as architecture. The interior of the Dome of the Stone (Jerusalem, circa 691), for case, features calligraphic inscriptions of verses from the Quran too as from additional sources. As in Europe in the Middle Ages , religious exhortations such as Quranic verses may exist included in secular objects, peculiarly coins, tiles, and metalwork .

Interior view of the Dome of the Stone: The interior of The Dome of the Rock features many calligraphic inscriptions, from both the Quran and other sources; it demonstrates the importance of calligraphy in Islamic art and its use in several different media.

Calligraphic inscriptions were not exclusive to the Quran, but also included verses of poetry or recorded ownership or donation. Calligraphers were highly regarded in Islam, which reinforces the importance of the word and its religious and artistic significance.

Islamic Book Painting

Manuscript painting in the late medieval Islamic globe reached its height in Persia, Syria, Iraq, and the Ottoman Empire.

Learning Objectives

Discuss the origin and development of Islamic manuscript painting

Key Takeaways

Cardinal Points

- The art of the Persian book was born under the Ilkhanid dynasty and encouraged past the patronage of aristocrats for big illuminated manuscripts .

- Islamic manuscript painting witnessed its first gilt historic period in the 13th century when information technology was influenced past the Byzantine visual vocabulary and combined with Mongol facial types from 12th-century book frontispieces.

- Under the dominion of the Safavids in Islamic republic of iran (1501 to 1786), the art of manuscript illumination achieves new heights, in item in the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp, an immense copy of Ferdowsi's epic poem that contains more than 250 paintings.

- The medieval Islamic texts called Maqamat were some of the earliest coffee-table books and among the first Islamic art to mirror daily life.

- Masterpieces of Ottoman manuscript illustration include the two books of festivals, i from the end of the 16th century and the other from the era of Sultan Murad Iii.

Central Terms

- Mongols: An umbrella term for a large grouping of Mongolic and Turkic tribes united under the rule of Genghis Khan in the 13th century.

- illuminated manuscripts: A book in which the text is supplemented by the addition of decoration, such as busy initials, borders (marginalia), and miniature illustrations.

- miniature: An illustration in an ancient or medieval illuminated manuscript.

- muraqqa: An anthology in book form containing Islamic miniature paintings and specimens of Islamic calligraphy, normally from several unlike sources, and perhaps other matter.

- Maqamat: The plural for Maqāma, an Arabic literary genre of rhymed prose with intervals of poetry that often ruminates on spiritual topics.

Islamic Volume Painting

Book painting in the late medieval Islamic world reached its height in Persia, Syria, Iraq, and the Ottoman Empire . The art class blossomed across the different regions and was inspired by a range of cultural reference points.

The evolution of book painting kickoff began in the 13th century, when the Mongols, under the leadership of Genghis Khan, swept through the Islamic world. Upon the death of Genghis Khan, his empire was divided among his sons and dynasties formed: the Yuan in China, the Ilkhanids in Islamic republic of iran, and the Golden Horde in northern Iran and southern Russia.

The Ilkhanids

The Ilkhanids were a rich civilization that developed under the petty khans in Iran. Architectural activity intensified equally the Mongols became sedentary nonetheless retained traces of their nomadic origins, such as the north–south orientation of buildings. Persian, Islamic, and East Asian traditions melded together during this period and a process of Iranization took place, in which construction co-ordinate to previously established types, such every bit the Iranian-plan mosques , was resumed.

The art of the Western farsi book was built-in under the Ilkhanid dynasty and encouraged past the patronage of aristocrats for big illuminated manuscripts, such as the Jami' al-tawarikh by Rashid-al-Din Hamadani. Islamic book painting witnessed its starting time golden age in the 13th century, mostly within Syrian arab republic and Republic of iraq.

Miniatures

The tradition of the Persian miniature (a small painting on paper) developed during this period, and it strongly influenced the Ottoman miniature of Turkey and the Mughal miniature in Republic of india. Considering illuminated manuscripts were an art of the court, and not seen in public, constraints on the depiction of the man figure were much more than relaxed and the homo form is represented with frequency inside this medium.

Influence from the Byzantine visual vocabulary (blue and aureate coloring, angelic and victorious motifs, symbology of drapery) was combined with Mongol facial types seen in 12th-century book frontispieces. Chinese influences in Islamic book painting include the early adoption of the vertical format natural to a volume. Motifs such as peonies, clouds, dragons, and phoenixes were adapted from Prc as well, and incorporated into manuscript illumination.

Mongol soldiers, in Jami al-tawarikh past Rashid-al-Din Hamadani: The Jāmi al-tawārīkh is a work of literature and history, produced by the Mongol Ilkhanate in Persia. The breadth of the work has caused information technology to be called the first world history and its lavish illustrations and calligraphy required the efforts of hundreds of scribes and artists.

The largest commissions of illustrated books were usually classics of Persian poetry, such as the Shahnameh. Under the rule of the Safavids in Islamic republic of iran (1501 to 1786), the art of manuscript illumination achieved new heights. The most noteworthy example of this is the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp, an immense re-create of Ferdowsi's epic poem that contains more 250 paintings.

The Court of Gayumars, from the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp: Illuminated manuscripts of the Shahnameh were frequently deputed past majestic patrons.

Maqamat and Albums

The medieval Islamic texts called Maqamat that were copied and illustrated by Yahya ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti, were some of the primeval coffee-table books. They were amongst the first texts in Islamic fine art to hold a mirror to daily life, portraying humorous stories and showing piffling adherence to prior pictorial traditions.

In the 17th century a new type of painting developed based around the album (muraqqa). The albums were the creations of connoisseurs who bound together single sheets of paintings, drawings, or calligraphy past various artists; they were sometimes excised from before books and other times created as independent works.

The paintings of Reza Abbasi effigy largely in this new class of book fine art. The grade depicts one or two larger figures, typically idealized beauties in a garden setting, and often use the grisaille techniques previously used for background border paintings .

Mughal and Ottoman Manuscripts

The Mughals and Ottomans both produced lavish manuscripts of more contempo history with the autobiographies of the Mughal emperors and purely military chronicles of Turkish conquests. Portraits of rulers adult in the 16th century, and later in Persia, where they became very popular.

Mughal portraits, commonly in profile, are very finely fatigued in a realist style , while the best Ottoman ones are vigorously stylized . Album miniatures typically featured picnic scenes, portraits of individuals, or (in India especially) animals, or arcadian youthful beauties of either sex.

Masterpieces of Ottoman manuscript illustration include the ii books of festivals, one from the end of the 16th century and the other from the era of Sultan Murad Iii. These books contain numerous illustrations and showroom a strong Safavid influence, perchance inspired by books captured in the course of the Ottoman–Safavid wars of the 16th century.

Islamic Ceramics

Islamic art has notable achievements in ceramics that reached heights unmatched past other cultures.

Learning Objectives

Discuss how developments such equally tin-opacified glazing and stonepaste ceramics made Islamic ceramics some of the most advanced of its time

Central Takeaways

Key Points

- The showtime Islamic opaque glazes date to around the 8th century, and some other significant contribution was the development of stonepaste ceramics in 9th century Republic of iraq.

- Lusterwares with irised colors were either invented or considerably developed in Persia and Syria from the 9th century onward.

- The techniques, shapes, and decorative motifs of Chinese ceramics were admired and emulated by Islamic potters, peculiarly after the Mongol and Timurid invasions.

- The Hispano–Moresque fashion emerged in the 8th century, with more refined product happening later, presumably by Muslim potters working in areas reconquered past Christian kingdoms.

Central Terms

- Hispano–Moresque style: A manner of Islamic pottery created in Al-Andaluz, or Muslim Spain, which continued to be produced under Christian rule in styles that blended Islamic and European elements.

- lusterware: A type of pottery or porcelain having an iridescent metallic glaze.

- coat: The vitreous coating of pottery or porcelain, or a transparent or semi-transparent layer of paint.

- ceramics: Inorganic, nonmetallic solids created by the action of heat and their subsequent cooling. Most common ceramics are crystalline and the earliest uses of ceramics were in pottery.

Islamic Ceramics

Islamic fine art has notable achievements in ceramics, both in pottery and tiles for buildings, which reached heights unmatched by other cultures . Early pottery had usually been unglazed, merely a tin-opacified glazing technique was adult past Islamic potters. The first Islamic opaque glazes tin be found as blue-painted ware in Basra, dating to around the 8th century.

Another significant contribution was the evolution of stonepaste ceramics, originating from ninth century Iraq. The first industrial circuitous for glass and pottery production was congenital in Ar-Raqqah, Syria, in the 8th century. Other centers for innovative pottery in the Islamic world included Fustat (from 975 to 1075), Damascus (from 1100 to effectually 1600), and Tabriz (from 1470 to 1550).

Lusterware

Lusterware is a type of pottery or porcelain that has an iridescent metallic coat. Luster showtime began as a painting technique in glassmaking , which was then translated to pottery in Mesopotamia in the ninth century.

tenth century dish: Islamic fine art has very notable achievements in ceramics, both in pottery and tiles for walls, which reached heights unmatched by other cultures. This dish is from Due east Persia or Central Asia.

The techniques, shapes, and decorative motifs of Chinese ceramics were admired and emulated past Islamic potters, peculiarly afterward the Mongol and Timurid invasions. Until the Early Modern menstruum, Western ceramics had trivial influence, merely Islamic pottery was highly sought after in Europe, and was often copied.

An instance of this is the albarello, a type of earthenware jar originally designed to concord apothecary ointments and dry drugs. The development of this blazon of pharmacy jar had its roots in the Islamic Center East. Hispano–Moresque examples were exported to Italy, inspiring the earliest Italian examples, from 15th century Florence.

Hispano–Moresque Way

The Hispano–Moresque style emerged in Al-Andaluz, or Muslim Spain, in the 8th century, under Egyptian influence. More than refined production happened much afterwards, presumably by Muslim potters who worked in the areas reconquered by the Christian kingdoms.

The Hispano–Moresque style mixed Islamic and European elements in its designs and was exported to neighboring European countries. The way introduced 2 ceramic techniques to Europe:

- Glazing with an opaque white tin-glaze.

- Painting in metallic lusters.

Ottoman Iznik pottery produced most of the finest ceramics of the 16th century—tiles and big vessels boldly decorated with floral motifs that were influenced by Chinese Yuan and Ming ceramics. These were yet in earthenware, since porcelain was not made in Islamic countries until modern times.

The medieval Islamic world as well painted pottery with animal and human being imagery . Examples are establish throughout the medieval Islamic world, particularly in Persia and Egypt.

Islamic Textiles

The most important textile produced in the Medieval and Early Modern Islamic Empires was the carpet.

Learning Objectives

Hash out the making and designs of Islamic textiles

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- The product and trade of textiles pre-dates Islam , and had long been of import to Middle Eastern cultures and cities, many of which flourished due to the Silk Route .

- When the Islamic dynasties formed and grew more powerful they gained control over cloth production in the region, which was arguably the most important craft of the era.

Fundamental Terms

- material arts: The production of craft that use found, animal, or synthetic fibers to create objects.

Islam and the Textile Arts

The textile arts refer to the product of arts and crafts that utilise plant, animal, or synthetic fibers to create objects. These objects can be for everyday utilise, or they can exist decorative and luxury items. The production and trade of textiles pre-dates Islam, and had long been of import to Center Eastern cultures and cities, many of which flourished due to the Silk Road.

When the Islamic dynasties formed and grew more powerful they gained control over textile production in the region, which was arguably the virtually important craft of the era. The most of import textile produced in Medieval and Early on Modern Islamic Empires was the carpet.

The Ottoman Empire and Carpet Production

The fine art of carpeting weaving was peculiarly important in the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman state was founded by Turkish tribes in northwestern Anatolia in 1299 and became an empire in 1453 after the momentous conquest of Constantinople.

Stretching beyond Asia, Europe, and Africa, the Empire was vast and long lived, lasting until 1922 when the monarchy was abolished in Turkey. Inside the Ottoman Empire, carpets were immensely valued as decorative furnishings and for their practical value . They were used not just on floors but also as wall and door hangings, where they provided additional insulation.

These intricately knotted carpets were made of silk, or a combination of silk and cotton, and were often rich in religious and other symbolism. Hereke silk carpets, which were fabricated in the coastal boondocks of Hereke, were the virtually valued of the Ottoman carpets because of their fine weave. The Hereke carpets were typically used to furnish imperial palaces.

Carpet and interior of the Harem room in Topkapi Palace, Istanbul: The Ottoman Turks were famed for the quality of their finely woven and intricately knotted silk carpets.

Persian Carpets

The Iranian Safavid Empire (1501–1786) is distinguished from the Mughal and Ottoman dynasties by the Shia organized religion of its shahs, which was the majority Islamic denomination in Persia. Safavid art is contributed to several aesthetic traditions, peculiarly to the textile arts.

In the sixteenth century, carpet weaving evolved from a nomadic and peasant craft to a well-executed industry that used specialized pattern and manufacturing techniques on quality fibers such as silk. The carpets of Ardabil, for case, were commissioned to commemorate the Safavid dynasty and are at present considered to be the best examples of classical Persian weaving, particularly for their use of graphical perspective.

Textiles became a large export, and Persian weaving became one of the most pop imported goods of Europe. Islamic carpets were a luxury item in Europe and there are several examples of European Renaissance paintings that document the presence of Islamic textiles in European homes during that time.

The Ardabil Rug, Persia, 1540: The Ardabil Carpet is the finest instance of 16th century Persian carpeting product.

Indonesian Batik

Islamic textile production, however, was non limited to the carpet. Royal factories were founded for the purpose of cloth product that likewise included cloth and garments.

The development and refinement of Indonesian batik cloth was closely linked to Islam. The Islamic prohibition on certain images encouraged batik design to get more abstract and intricate. Realistic depictions of animals and humans are rare on traditional batik, but serpents, puppet-shaped humans, and the Garuda of pre-Islamic mythology are all commonplace.

Although its existence in Indonesia pre-dates Islam, batik reached its high point in the royal Muslim courts, such as Mataram and Yogyakarta, whose Muslim rulers encouraged and patronized batik production. Today, batik has undergone a revival, and cloths are used for other purposes besides wearing, such as wrapping the Quran.

Javanese courtroom batik: The development and refinement of Indonesian batik cloth was closely linked to Islam.

Source: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-arthistory/chapter/introduction-to-islamic-art/

0 Response to "Which of the Following Is Not a Correct Statement About Islamic Art?"

Post a Comment